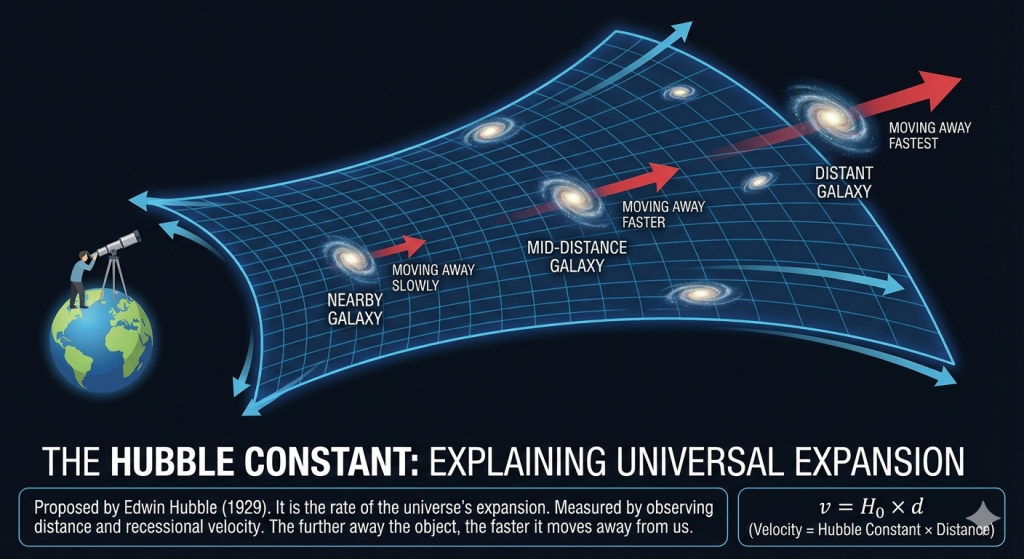

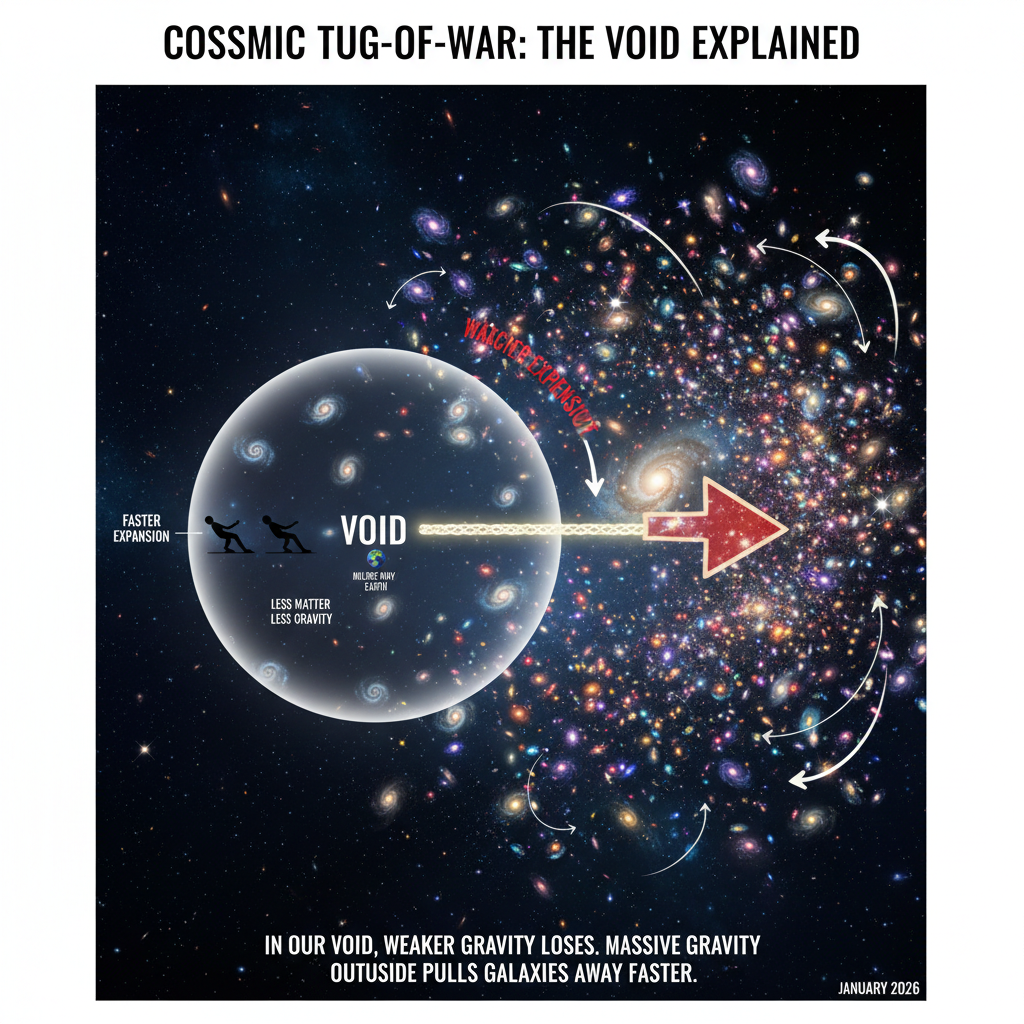

In my last post, we looked at the possibility that we’re living in a giant cosmic ghost town, a 2-billion-light-year void. It’s a compelling idea because it explains why our “Local Team” sees the universe rushing away so quickly without breaking the laws of physics.

But as I read further, I realized the plot thickens. Even if the “void” explains part of the mystery, we still have to ask: Is our equipment lying to us?

Checking Hubble’s Homework

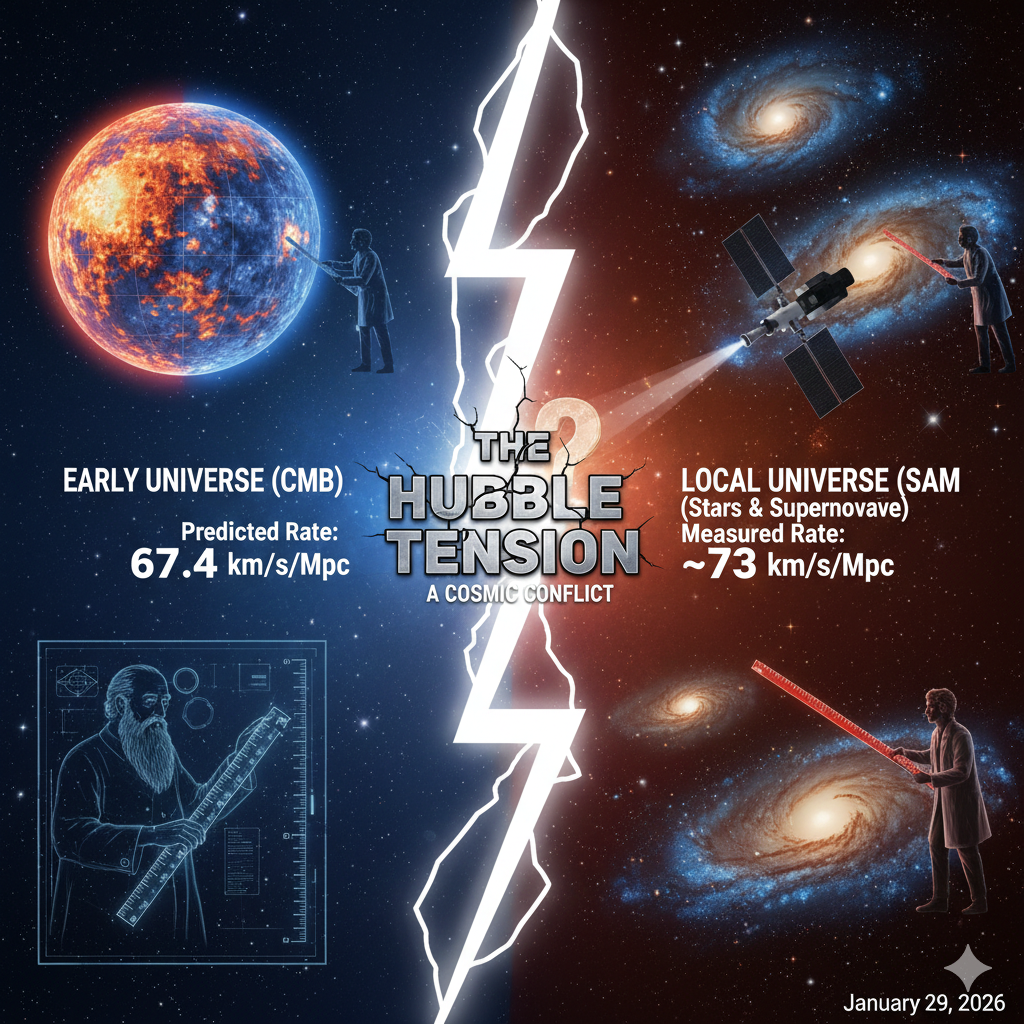

My first thought was similar to what NASA had: “Maybe the Hubble Space Telescope is just getting old and blurry?” After all, it was launched in the early 1990’s, around 35 years back. Perhaps it’s miscounting stars or confusing distant galaxies with their neighbors (an effect called “crowding”), making them look closer than they really are.

But unlike me, NASA sent in the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to settle this. One of Webb’s secret missions was to “check the homework” of the Hubble Telescope. So, in 2024-2025, Webb looked at the same stars Hubble did, but with much sharper infrared eyes. The results were a blow to people like me who were hoping for a simple mistake. It turns out, Hubble was right. The measurements were rock solid. The “crowding” wasn’t the issue. The universe really is expanding faster in our neighborhood.

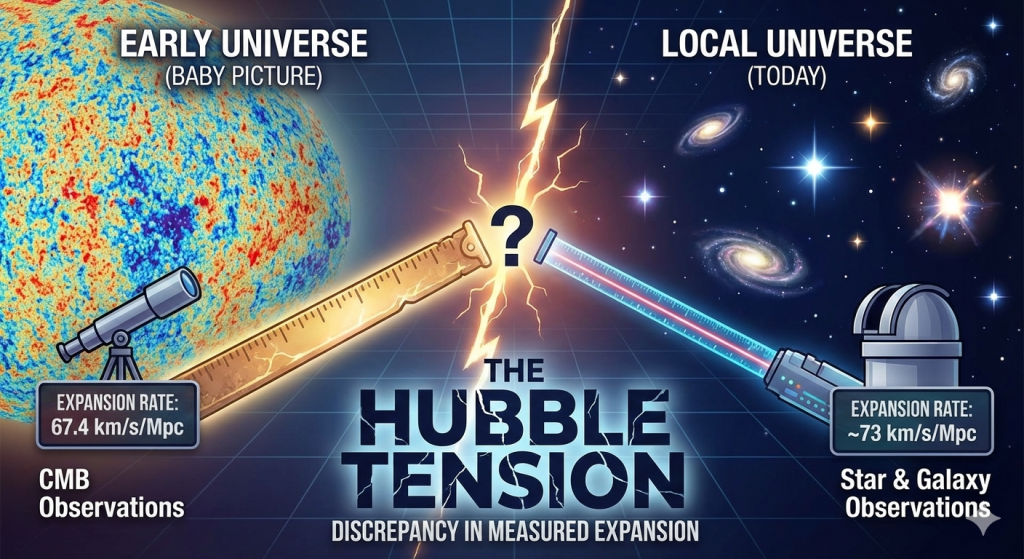

The Great Data Civil War

Just when it seemed the “Local Team” had won, a new twist emerged. A separate group, the Chicago-Carnegie program, used a totally different type of star, JAGB stars (J-region Asymptotic Giant Branch stars) to measure the same distance. The result? The JAGB stars gave a speed of ~67.9 km/s/Mpc. Now, this matches the “Baby Picture” team (the Early Universe), not the Local team!

The JAGB stars are aging, “sooty” red giant stars that have entered a very specific phase of life. They are called carbon-rich giants because they’ve dredged up so much carbon from their cores that it creates a “smoky” atmosphere. For astronomers, they are the perfect “standard candles.” Because these stars have a very consistent, predictable brightness in the near-infrared, they act like a cosmic lightbulb of a known wattage. If we know how bright they should be, we can compare their actual brightness to calculate exactly how far away their galaxy is. Unlike other stars that can be finicky or hidden by dust, JAGB stars are bright, easy to spot, and incredibly reliable. This is why it’s so shocking that they’re currently giving us a different answer than the other “Local” teams!

So now, we have a literal “civil war” in the data. One reliable method says the universe is sprinting at 73+, while another equally reliable method says it’s cruising at 67. JWST was supposed to solve the problem; instead, it proved that the problem is even deeper than we imagined.

The Ghost in the Machine

If the measurements are all correct, then our understanding of physics must be wrong. I started looking into the leading theory of Early Dark Energy (EDE).

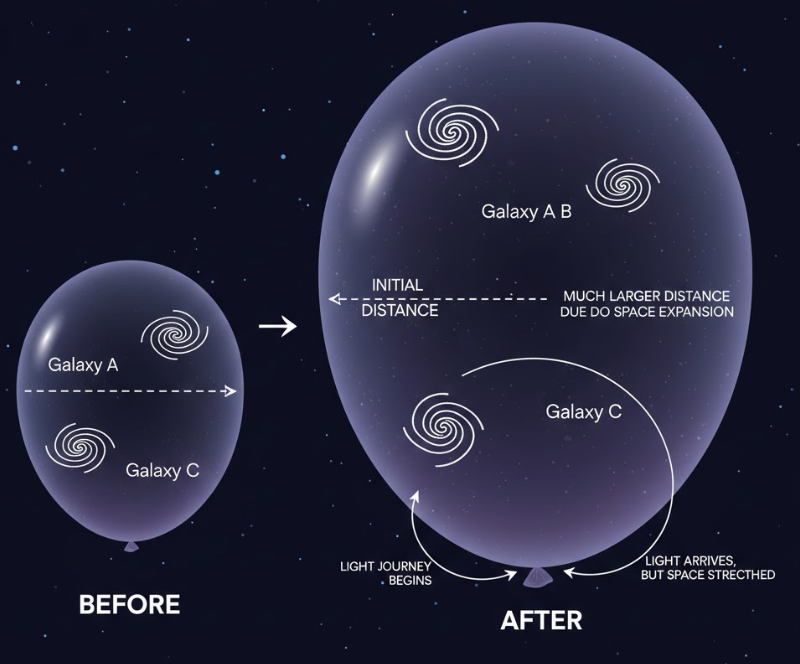

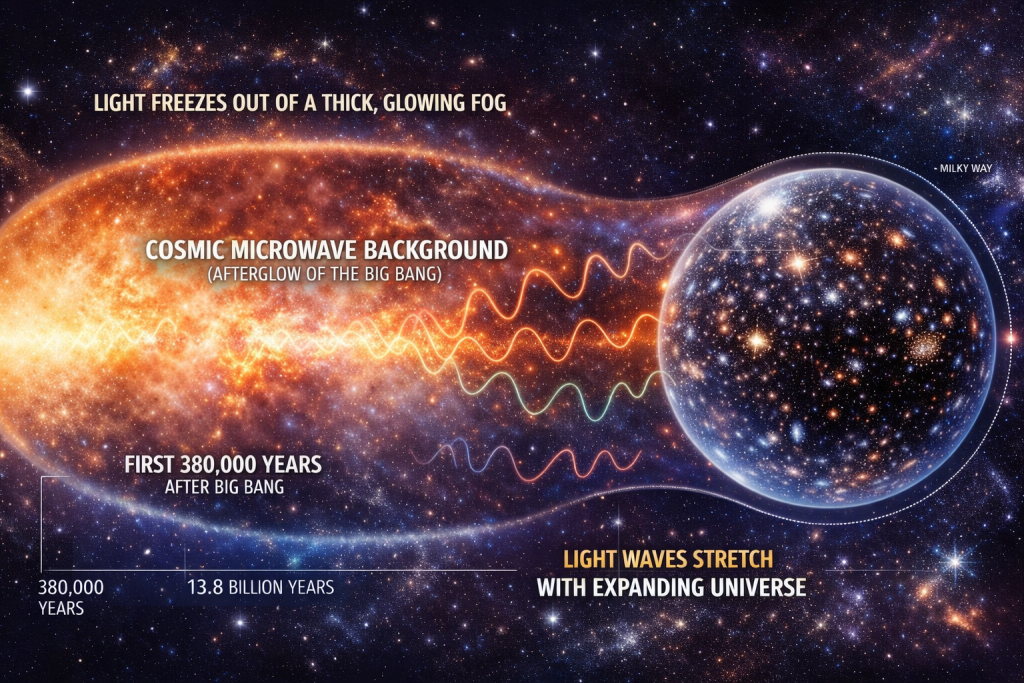

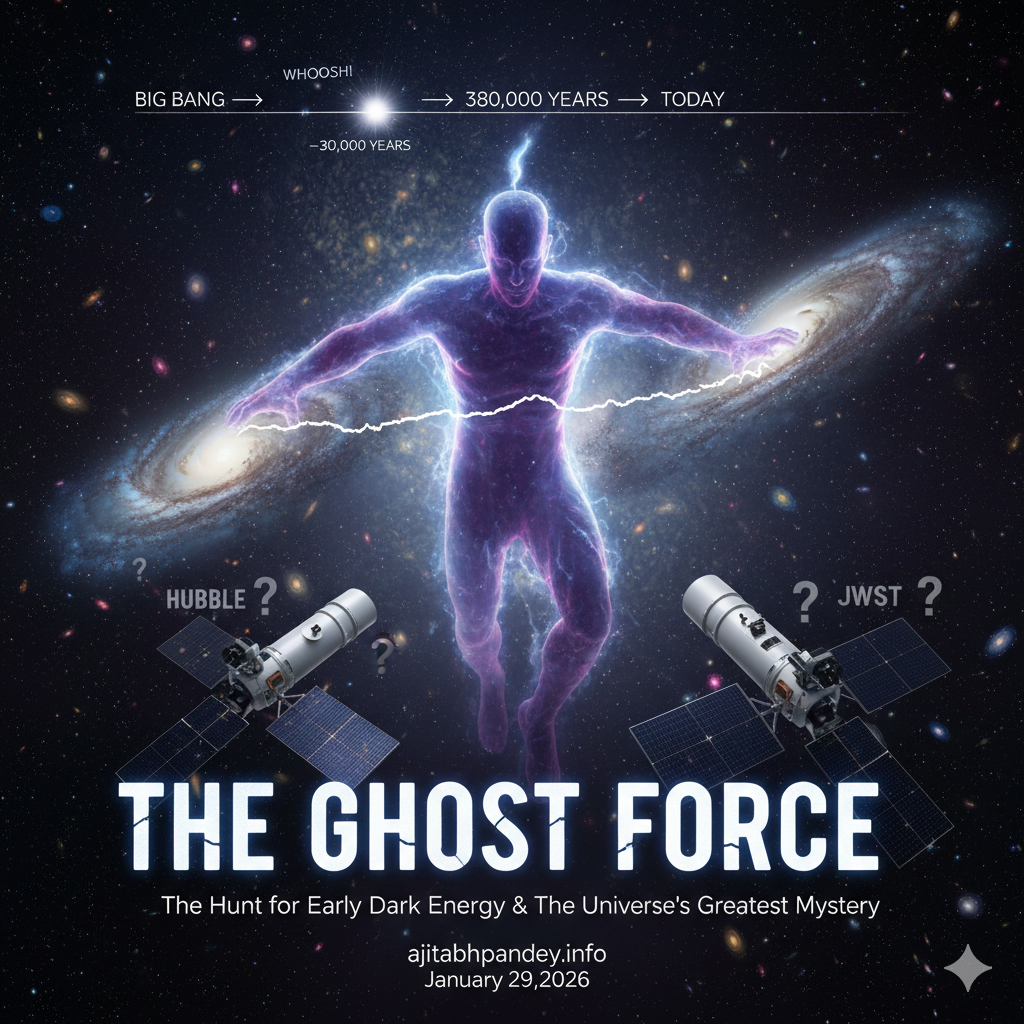

“Dark Energy” is the invisible force pushing the universe apart today. But some physicists think there was a second, hidden burst of energy right after the Big Bang, specifically around 380,000 years in.

Imagine the universe was expanding normally, and then – WHOOSH – a temporary “ghost” energy field kicked in, shoved everything apart faster for a few millennia, and then vanished without a trace.

This “Early Dark Energy” would essentially “shrink the ruler” we use to measure the cosmos. If the ruler we use for the early universe is actually smaller than we thought, the faster speeds we see today would suddenly make perfect sense. The Tension would vanish.

The Catch

It’s a beautiful theory, but reality is proving to be a harsh critic. New data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) released recently is making it hard for this “ghost” energy to fit the facts. The data suggests that if this energy existed, it had to be so incredibly precise that it’s almost “too lucky” to be true.

We are left with a universe that potentially had a massive growth spurt we can’t explain, driven by a force we can’t find.

Whether we are living in a Cosmic Void, or witnessing the remnants of Early Dark Energy, one thing is clear: our “Standard Model” of the universe is missing a few chapters. We’re living in a cosmic ghost town, watching a ghost force, waiting for the next big discovery to tell us where we truly stand.

References:

- The Chicago-Carnegie Hubble Program: JWST JAGB Extragalactic Distance Scale (Freedman, W. L., et al., 2024/2025)

- DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from BAO (DESI Collaboration, 2024/2025)