If you’ve been managing systems since the days of AT&T Unix System V Release 3 (SVR3), you remember when networking was a manual affair. Name resolution often meant a massive, hand-curated /etc/hosts file and a prayer.

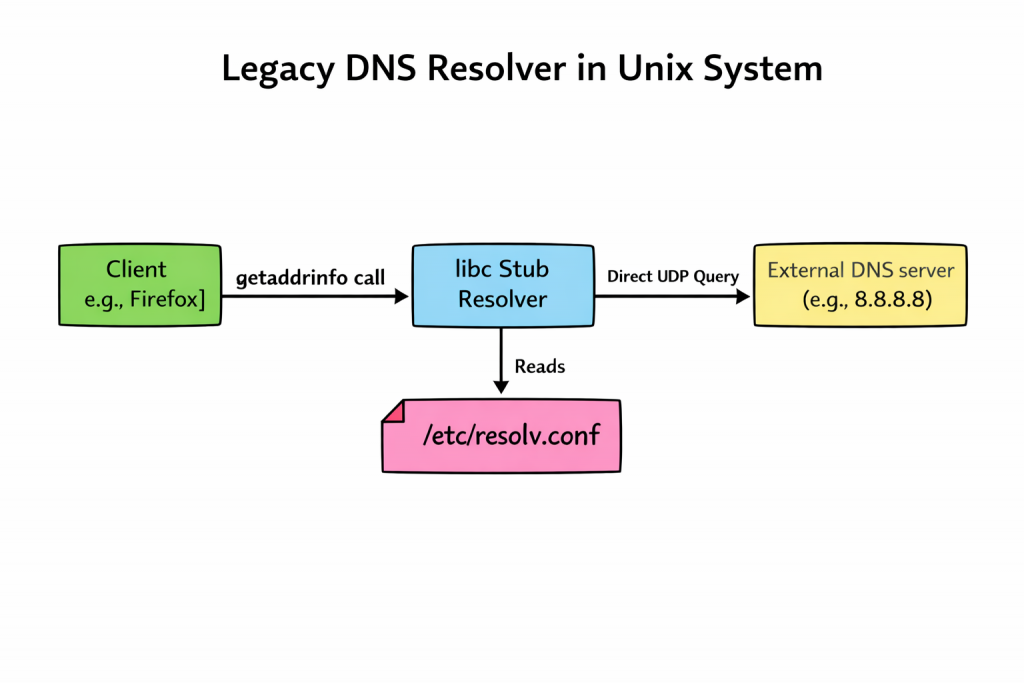

As the Domain Name System (DNS) matured, the standard consolidated around a single, universally understood text file: /etc/resolv.conf. For decades, that file served us well. But the requirements of modern, dynamic networking, involving laptops hopping Wi-Fi SSIDs, complex VPN split-tunnels, and DNSSEC validation, forced a massive architectural shift in the Linux world, most notably in the form of systemd-resolved.

Let’s walk through history, with hands-on examples, to see how we got here.

AT&T SVR3: The Pre-DNS Era

Released around 1987-88, SVR3 was still rooted in the hosts file model. The networking stacks were primitive, and TCP/IP was available but not always bundled. I still remember that around 1996-97, I used to install AT&T SVR3 version 4.2 using multiple 5.25-inch DSDD floppy disks, then, after installation, use another set of disks to install the TCP/IP stack. DNS support was not native, and we relied on /etc/hosts for hostname resolution. By SVR3.2, AT&T started shipping optional resolver libraries, but these were not standardized.

# Example /etc/hosts file on SVR3

127.0.0.1 localhost

192.168.1.10 svr3box svr3box.localIf DNS libraries were installed, /etc/resolv.conf could be used:

# /etc/resolv.conf available when DNS libraries were installed

nameserver 192.168.1.1

domain corp.example.comdig did not exists then, and we used to use nslookup.

nslookup svr3box

Server: 192.168.1.1

Address: 192.168.1.1#53

Name: svr3box.corp.example.com

Address: 192.168.1.10Solaris Bridging Classical and Modern

When I was introduced to Sun Solaris around 2003-2005, I realized that DNS resolution was very well structured (at least compared to the SVR3 systems I had worked on earlier). Mostly, I remember working on Solaris 8 (with a few older SunOS 5.x systems). These systems required both /etc/resolv.conf and /etc/nsswitch.conf

# /etc/nsswitch.conf

hosts: files dns nisThis /etc/nsswitch.conf had only the job of instructing the libc C library to look in /etc/hosts, then DNS, and then NIS. Of course, you can change the sequence.

The /etc/resolv.conf defined the nameservers –

nameserver 8.8.8.8

nameserver 1.1.1.1

search corp.example.comSolaris 11 introduced SMF (Service Management Facility), and this allowed the /etc/resolv.conf to auto-generate based on the SMF profile. Manual edits were discouraged, and we were learning to use:

svccfg -s dns/client setprop config/nameserver=8.8.8.8

svcadm refresh dns/clientFor me, this marked the shift from text files to managed services, although I did not work much on these systems.

BSD Unix: Conservatism and Security

The BSD philosophy is simplicity, transparency and security-first.

FreeBSD and NetBSD still rely on /etc/resolv.conf file and the dhclient update the file automatically. This helps in very straightforward debugging.

cat /etc/resolv.conf

nameserver 192.168.1.2

nslookup freebsd.org

OpenBSD, famous for its “secure by default” stance, includes modern, secure DNS software like unbound in its base installation; its default system resolution behavior remains classical. Unless the OS is explicitly configured to use a local caching daemon, applications on a fresh OpenBSD install still read /etc/resolv.conf and talk directly to external servers. They prioritize a simple, auditable baseline over complex automated magic.

The Modern Linux Shift

On modern Linux distributions (Ubuntu 18.04+, Fedora, RHEL 8+, etc.), the old way of simply “echoing” a nameserver into a static /etc/resolv.conf file is effectively dead. The reason for this is that the old model couldn’t handle race conditions. If NetworkManager, a VPN client, and a DHCP client all tried to write to that single file at the same time, the last one to write won.

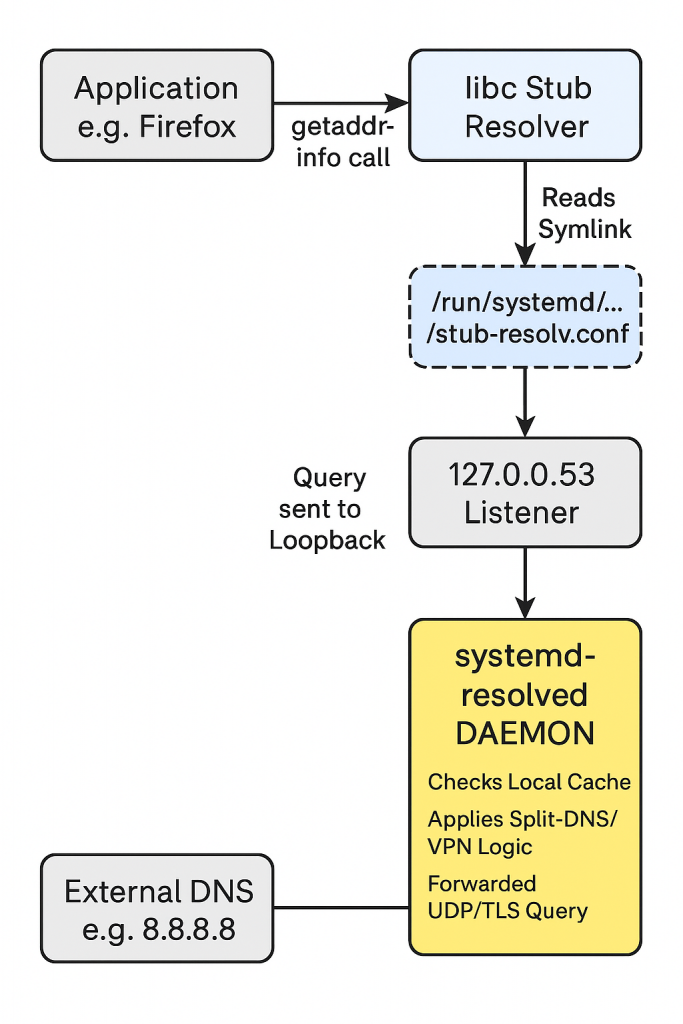

In modern linux systems, systemd-resolved acts as a local middleman, a DNS broker that manages configurations from different sources dynamically. The /etc/resolv.conf file is no longer a real file; it’s usually a symbolic link pointing to a file managed by systemd that directs local traffic to a local listener on 127.0.0.53.

systemd-resolved adds features like –

- Split-DNS to help route VPN domains seperately.

- Local-Caching for faster repeated lookups.

- DNS-over-TLS for encrypted queries.

ls -l /etc/resolv.conf

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 39 Dec 24 11:00 /etc/resolv.conf -> ../run/systemd/resolve/stub-resolv.confThis complexity buys us features needed for modern mobile computing: per-interface DNS settings, local caching to speed up browsing, and seamless VPN integration.

The modern linux systems uses dig and resolvectl for diagnostics:

$ dig @127.0.0.53 example.com

; <<>> DiG 9.16.50-Raspbian <<>> @127.0.0.53 example.com

; (1 server found)

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 17367

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;example.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

example.com. 268 IN A 104.18.27.120

example.com. 268 IN A 104.18.26.120

;; Query time: 9 msec

;; SERVER: 127.0.0.53#53(127.0.0.53)

;; WHEN: Wed Dec 24 12:49:43 IST 2025

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 72

$ resolvectl query example.com

example.com: 2606:4700::6812:1b78

2606:4700::6812:1a78

104.18.27.120

104.18.26.120

-- Information acquired via protocol DNS in 88.0ms.

-- Data is authenticated: no; Data was acquired via local or encrypted transport: no

-- Data from: networkBecause editing the file directly no longer works reliably, we must use tools that communicate with the systemd-resolved daemon.

Suppose you want to force your primary ethernet interface (eth0) to bypass DHCP DNS and use Google’s servers temporarily:

sudo systemd-resolve --set-dns=8.8.8.8 --set-dns=8.8.4.4 --interface=eth0To check what is actually happening—seeing which DNS servers are bound to which interface scopes—run:

systemd-resolve --statusand to clear the manual overrides and go back to whatever setting DHCP provided:

sudo systemd-resolve --revert --interface=eth0We’ve come a long way from System V R3. While the simplicity of the classical text-file approach is nostalgic for those of us who grew up on it, the dynamic nature of today’s networking requires a smarter local resolver daemon. It adds complexity, but it’s the price we pay for seamless connectivity in a mobile world.